The Rate of Fusion

If you haven’t read The Basics of Fusion, I highly recommend you read it first before continuing on. If not, here’s a quick recap on what you missed:

RECAP

- Fusion is the combining of two hydrogen isotopes, often Deuterium and Tritium, to release an immense amount of energy

- Binding energy is the amount of energy released when a nuclei is separated into its component parts \(E=mc^2\)

- The binding energy curve and \(E=mc^2\) shows that combining two light nuclei into a nuclei with a higher binding energy releases LOTS of energy

- The Coulomb Force, a repulsive force between two like charged particles, prevents nuclei from fusing and increases the closer the two nuclei are to each other

- At a certain distance called the Coulomb Barrier, the nuclear strong force overtakes the Coulomb Force and allows fusion to occur. It’s an attractive short range forces that binds the nucleons (protons and neutrons in a nucleus together)

- For a particle to overcome the Coulomb Barrier, an immense amount of energy measured by the Coulomb Barrier’s height is needed. Sometimes, particles can tunnel through the barrier without enough to energy. Even so, this is what makes fusion difficult.

Now that we’ve gone through some of the basics of what fusion is, we’re going to calculate how often fusion occurs.

Average Distance Before Collision

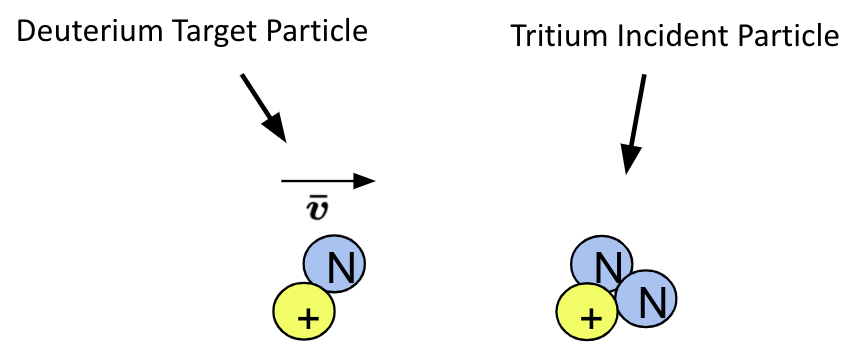

Imagine this: Deuterium nuclei are moving at a velocity \(v\) towards a stationary Tritium nucleus. The Tritium nucleus is the target particle and the Deuterium nuclei are the incident particles

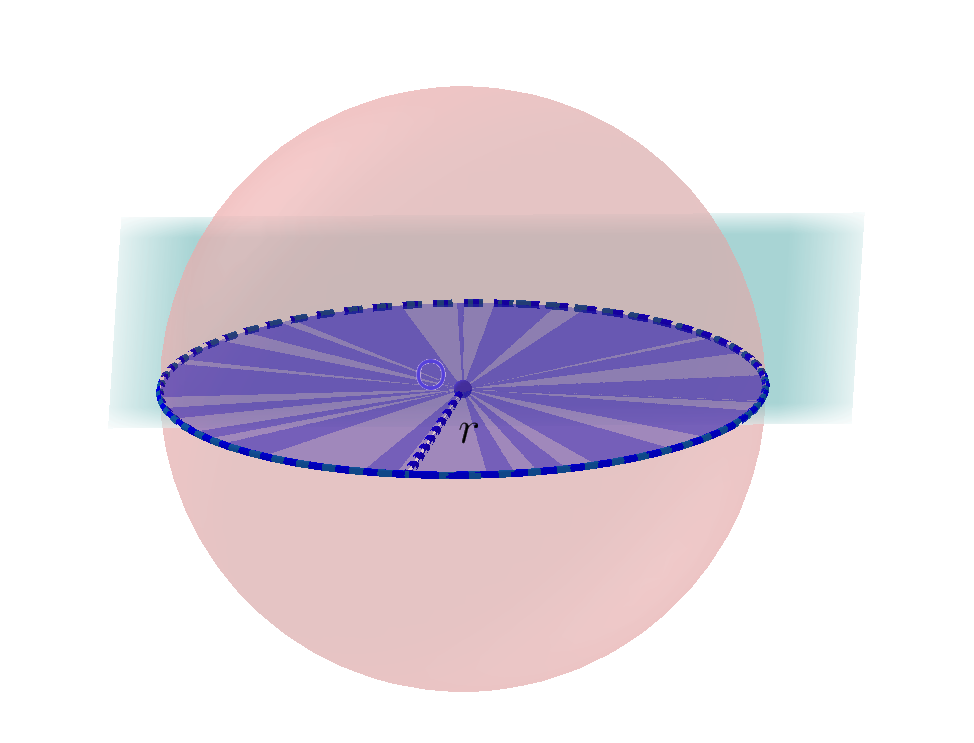

Each target particle takes up a certain amount of area in the cylinder called the cross sectional area. If we were to take a spherical particle divide it in half and then measure the area of the sphere on it’s half, this would be the cross sectional area \(\sigma\) of that particle.

If the incident particle passes through the cross sectional area \(\sigma\), then fusion occurs and this reaction is called a collision. If the incident particle does not, fusion will not occur.

You would think that if the target particle has a really large cross sectional area \(\sigma\), then the probability of a fusion reaction occurring would increase as well right? That’s correct - but we’re going to see exactly how the cross sectional area \(\sigma\) is related to the probability of fusion occurring by calculating the Mean Free Path. The Mean Free Path is the average distance a particle travels before fusion occurs.

The Mean Free Path

Before we calculate the Mean Free Path, we’ll need to calculate the probability \(P\) that Deuterium and Tritium will fuse in the cylinder volume. This will become a variable in the equation for The Mean Free Path.

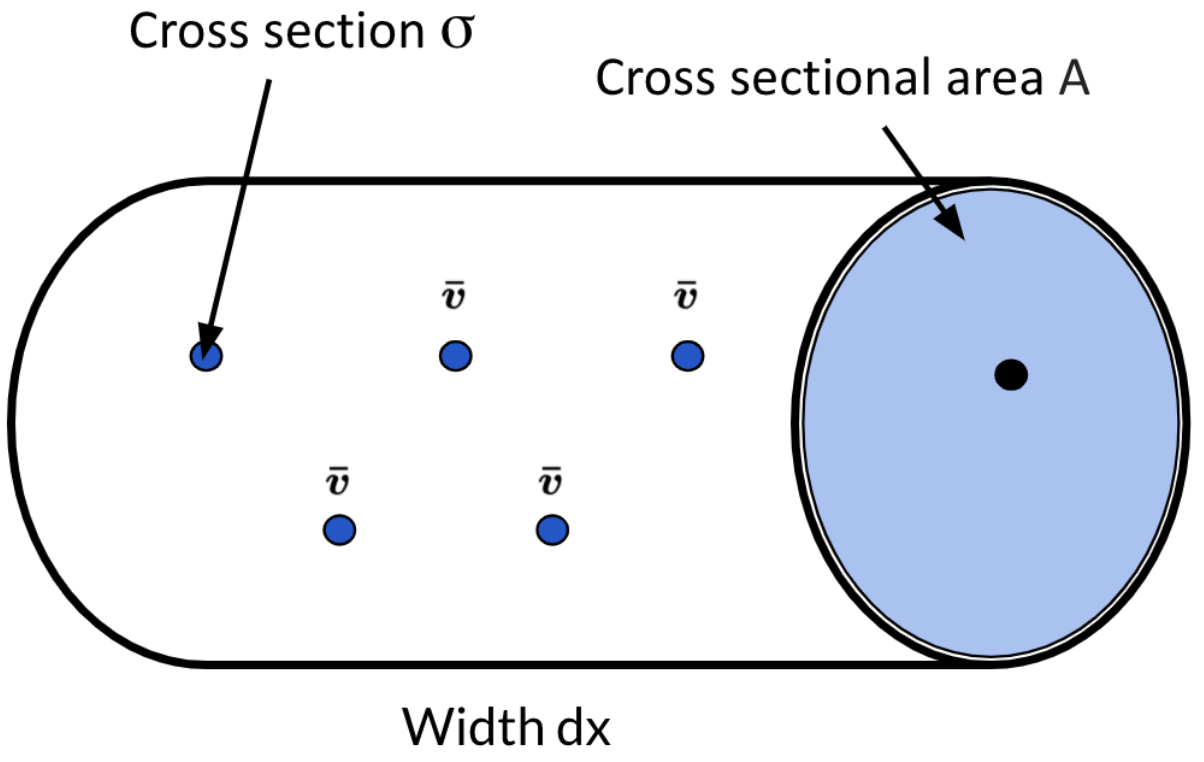

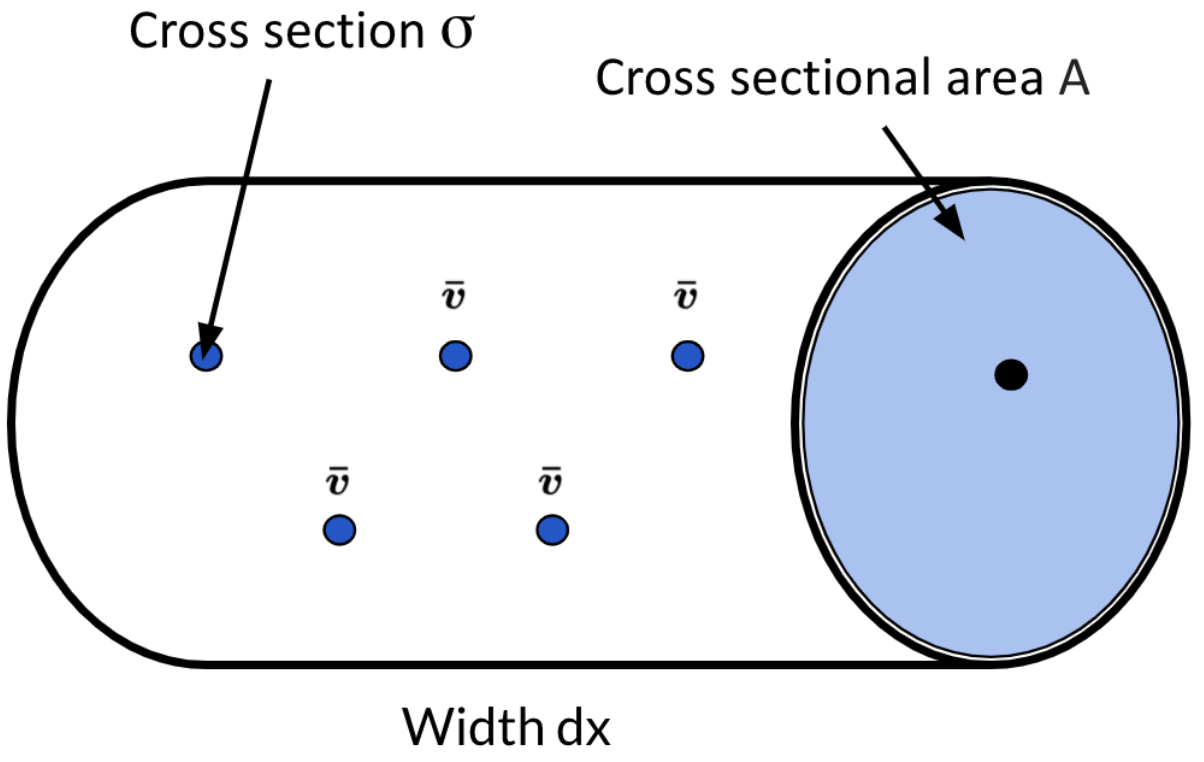

Remember the target (Tritium nuclei) and incident (Deuterium nuclei) particles. Well now there’s a cylinder filled with target particles that each have a cross sectional area \(\sigma\).

The cross sectional area of the cylinder is \(A\) and the width of the cylinder is \(dx\). From this, we know that the volume of the entire cylinder is \(V=Adx\)

If the density of the target particles in the cylinder is \(n_1\), then the total number of particles in the cylinder would be \(T_1=n_1V=n_1Adx\) (the density of the particles x volume of the cylinder)

If we wanted to know the fraction of the total area blocked by target particles it would be \(P =\frac{\sigma T_1}{A}= \frac {\sigma n_1 A dx}{A} = n_1dx\sigma\). We just took the total area the target particles take up and divided it by the cross sectional area of the sphere which gave us the area that the target particles take up in \(A\), the area of the cylinder.

We can use \(P\) to represent the probability of an incident particle fusing when it crosses \(dx\) by simply dividing it by \(dx\) = \(\frac {n_1dx\sigma}{dx}= n_1\sigma\).

What does this tell us about the probability of an incident particle fusing with a target particle?

- If the target particles have a larger cross sectional area \(\sigma\), then the probability of fusion occurring increases. Likewise, if the target particle has a smaller cross sectional area \(\sigma\), then the probability of fusion decreases

- If the density of the target particles in the cylinder \(n_1\) increases, the probability of fusion also increases. Likewise, if the density is smaller, the probability of fusion will also decrease.

Finally, we can calculate the Mean Free Path which will tell us the average distance a Deuterium particle has to travel before fusion occurs.

Let’s say that there are several incident particles with density \(n_2\). Don’t confuse this with \(n_1\) which we used to represent the density of the target particles.

We’ll use \(n_2\) to calculate the flux \(\Gamma\) — this is total number of incident particles crossing the cross sectional Area \(A\), per unit time per unit area. Don’t get impatient, we’re going to use this quantity to calculate the Mean Free Path shortly.

To calculate the flux, we took the total number of incident particles \(T_2\) and divided by area \(A\) and time \(dt\).

\[\Gamma = \frac{N_2}{Adt}=\frac{n_2Avdt}{Adt}=n_2v\]

This is just total number of incident particles, what portion of these particles are having a collision and fusing? We’ll represent the amount of particles that will fuse with \(d\gamma\). It’s equal to the probability that particles will fuse multiplied by the flux (total number of incident particles per area per time) Simple right?

\[d\gamma = P\Gamma = \sigma n_1 \Gamma dx\]

From this, we can also figure out the number of particles that are not having a collision and thus, not fusing.

\[ \Gamma = -\sigma n_1 \Gamma dx\]

\[\Gamma = \Gamma_0 e^{\frac{-x}{\gamma_m}}\]

where, The Mean Free Path is

\[ \gamma_m = \frac{1}{n_1 \sigma}\]

What Does This Tell Us About The Mean Free Path?

First, the Mean Free Path describes the average distance a particle must travel before a collision or fusion occurs.

- The equation tells us that as the density and the cross sectional area of the target particle increases, the distance the nuclei must travel before fusion occurs decreases. If the density and cross sectional area of the target particle decreases, the nuclei must travel a longer distance before collision can occur.

- It also shows the ‘e-folding decay length of the incident flux that has not undergo a collision’. Put in plain English, it means that the mean free path of an incident particle that has not undergone collision decreases by a factor of \(e\)

How Often Does Fusion Occur?

In this article I won’t be deriving the collision frequency but I’ll tell you how it’s related to the cross sectional area of the target particles \(\sigma\), the density of those particles \(n_1\) and the velocity of the particles.

\(v_m\) represents the Collision frequency

\(\tau_m\) represents the mean time between collisions

The Mean free path told us that a particle will travel a distance \(\\gamma_m\) before having a collision.

So the average time a collision takes to occur is the average distance before a collision \(\gamma_m\) divided by how often collisions occur \(v_m\).

\[\tau_m = \frac{\gamma_m}{v_m}=\frac{1}{n_1\sigma v}\]

So if we were to increase the density of the target particles, the cross sectional area of those particles and their velocity, the time between collisions would decrease.

The collision frequency is the inverse of this:

\[v_m = \frac{1}{\tau_m}=n_1\sigma v\]

In this case, let’s say we increased the density of the target particles, their cross sectional areas \(\sigma\) and their velocities, the collision frequency would increase. The opposite is also true.

Fusion Power Energy Density

The reaction rate \(R\) tells us how many times fusion occurs per unit time per unit volume. By calculating the reaction rate, we can then figure out how much energy fusion outputs per volume. This is important because it’ll let us know if the fusion reactions we’re using are capable of producing net positive energy … which is the entire point of using fusion energy in the first place. To produce immense amounts of clean energy.

In time \(dt=\frac{dx}{v}\) (this is time = distance particles travel / velocity) \(n_2Adx\) particles will pass through the target volume. Just to refresh your memory, the total number of particles passing through the target volume is the density of those particles \(n_2\) multiplied by the cross sectional area of the cylinder \(A\) multiplied by the width of the cylinder \(dx\). All we did here is take the volume of the space the particles are in multiplied by the density of those particles in that space to find the total number of particles. If this isn’t clicking, check here to refresh your memory.

In time \(dt=\frac{dx}{v}\) (this is time = distance particles travel / velocity) \(n_2Adx\) particles will pass through the target volume. Just to refresh your memory, the total number of particles passing through the target volume is the density of those particles \(n_2\) multiplied by the cross sectional area of the cylinder \(A\) multiplied by the width of the cylinder \(dx\). All we did here is take the volume of the space the particles are in multiplied by the density of those particles in that space to find the total number of particles. If this isn’t clicking, check here to refresh your memory.

The number of particles that will actually have a collision is the probability of having a collision \(P\) multiplied by the total number of particles \(n_2Adx\). → \(P(n_2Adx)\) So if there’s a higher probability of having a collision or a greater number of total particles, the number of particles having a collision will increase.

The reaction rate \(R\) is the number of particles having a collision \(P(n_2Adx)\) divided by the total Volume of the space the particles are in \((A dx)\) and the time \(dt\). The reaction rate is telling us how many fusion collisions are occurring per unit volume per time.

\[R = \frac{P(n_2Adx)}{Adxdt}=\sigma n_1 n_2 \frac{dx}{dt}=\sigma v n_1 n_2\]

Let’s say that each fusion reaction creates some energy \(E\), then the total energy produced in this reaction per unit volume is \(ER\)

Therefore, the power density of that fusion reaction in \(Watts/m^3\) is

\(S = ER=E n_1\sigma n_2 v\)

Now we can start to see how everything is related.

Let’s test what you learned from this section:

What would happen to the power density if I increased the density of the particles?

First, more fusion collisions would be occurring per in that space so the reaction rate \(R\) increases. Since the reaction rate increases, the power energy density \(S_j\) also increases. We would be producing more power per unit volume because more fusion collisions occur.

What would happen to the power density if the cross section of the nuclei decreased?

If the cross sectional area of the nuclei \(\sigma\) decreased, the number of collisions occurring in that volume of space \(R\) would decrease because there’s less available area for the particles to collide at. This would then decrease the power energy density \(S_j\) because less fusion collisions are occurring per unit volume.

What would happen to power density if the velocity of the particles was 0?

The power density would be 0 then, we would be producing no energy. If you were to set all the \(v\) terms to 0, the reaction rate \(R\) would equal 0. Plugging this into \(S_j\), we would get 0 as well. Particles need to be moving for for any collision to occur. If you wanted to count how many cars crashed on a highway but none of the cars were moving, then there would be 0 collisions right? Same thing for fusion, particles must be moving at a non zero velocity at least.

In every equation you’ve seem above, the velocity of the particles \(v\) has remained constant. In a real nuclear reactor, this definitely wouldn’t be the case. Particles would be moving at various speeds depending on how energetic they are.

Modifying The Reaction Rate

We need a way to include all the different velocities of particles in our reaction rate \(R=n_1n_2\sigma v\)

To do this we can create a function \(f\) that tells us the density of the particles and has all the information about the varying velocities of these particles.This is different from our normal density variable \(n\) that only included one velocity \(v\) to describe the velocity of all the particles.

I’ll walk you through this function using this scenario:

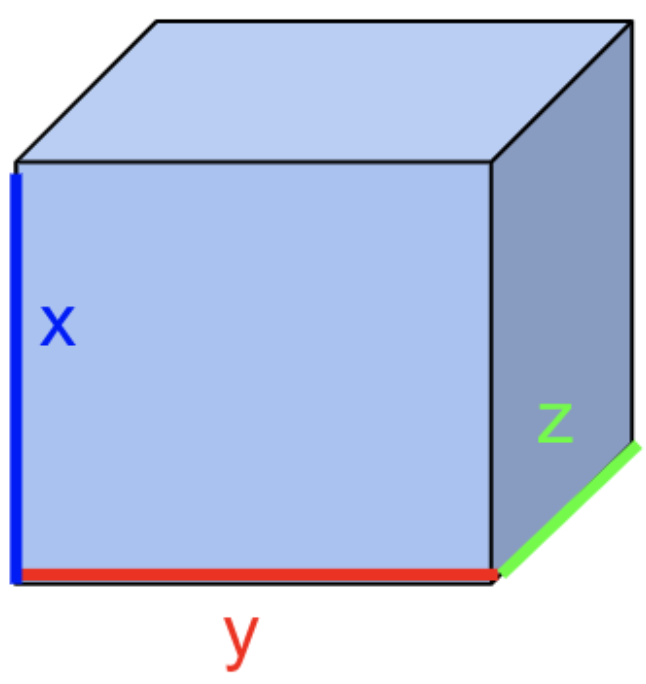

We have a small cubic volume of space \(dr=dxdydz\)

The total number of particles at a specific time \(t\) using our simpler density variable \(n\) would be \(n(r,t)dr\). The density is a function of the time and the volume of the cube space we’re looking at.

Let’s say there are 6 groups of velocities:

\(v_x\) and \(v_x + dv_x\),

\(v_y\) and \(v_y + dv_y\),

\(v_z\) and \(v_z + dv_y\)

To include all these velocity subgroups in our density function \(f\), we can take the 3 dimensions we were originally working in \(dr=dxdydz\) and instead upgrade it to a 6 dimensional space to include all the velocities. First, understand that \(drdv=(dzdydz) \cdot (dv_z dv_y dv_x)\) ← 6 dimensions. The density function then looks like this: \(f(r,v,t)drdv\)

Now we can find the total number of particles in a certain velocity group, let’s say \(dv\) by integrating over all the velocities and dividing it by the cubic volume \(dr=dxdydz\)

\[n(r,t) = \frac {dxdydz \int fdv_xdv_ydv_z}{dxdydz}= \int fdv\]

If we wanted to calculate the specific average velocity of a particle at \(dr\). We would do the following:

- Choose the subset of velocities \(v\)

- Multiply by the number of particles moving at the velocity

- Integrate over all possible values of \(v\)

- Divide by the total number of particles in \(dr\)

\[u(r,t)= \frac {dr \int vfdr}{ndr}= \frac {1}{n} \int vfdv\]

We can finally generalize the reaction rate \(R\) to include multiple velocities.

Remember that \(R= n_1n_2\sigma v\) with one velocity \(v\) for all the particles

- Replace the density of the target particles \(n_1\) with \(f_1(r,v_2,t)dv_1\)

- Replace the density of the incident particles \(n_2\) with \(f(r,v_2,t)dv_2\)

- Replace \(v\) with a relative velocity \(\mid v_2 - v_1 \mid\) which is the difference in velocity between the incident particles and the target particles

- Let \(\sigma = \sigma (\mid v_2 - v_1 \mid)\). This makes cross section directly related to the velocity between incident and target particles.

Important Things To Note:

- The velocity between the target and incident particles is very small, the cross section of those particles is also very small.

- When the velocities of incident and target particles are small, the coulomb force deflects the orbits of these particles and prevents the particles from getting close to each other to make a collision

- Which is why we need the target and incident particle to be travelling at high velocities so that the Coulomb Force can have less influence on the particles and allow them to fuse.

Final Generalized Reaction Rate

Substituting all the variables above, we finally have a reaction rate that tells us the number of particles colliding given the varying velocities of target and incident particles.

\[R = \int f_1(v_1)f_2(v_2) \sigma( \mid v_2 - v_1 \mid) \mid v_2 - v_1 \mid dv_1 dv_2\]

Thanks for reading! If you have any feedback or suggestions, I’d really appreciate it if you DM’d me on Twitter

For finishing, you can have some non-alcoholic 🍹 🍷(sorry, I’m 17 :P).

FINAL RECAP:

- Deuterium nuclei are target particles and Tritium nuclei are incident particles

- For fusion to occur, a target particle must collide with an incident particle

- The Mean Free Path tells us the average distance particles travel before fusion occurs. If the density of the particles and the cross sectional area of the particles increases, then the distance particles need to travel to collide will decrease.

- The collision frequency tells us how often fusion occurs. When the density and cross sectional area of target particles increases, the collision frequency will also increase

- The Power Energy Density of fusion tells us how much energy fusion produces per unit volume. It’s dependent on the amount of energy that is released in one collision, the density of target and incident particles, the velocity of those particles and their cross sectional area.

- In a realistic scenario, the target and incident particles are moving at different velocities. We can generalize the reaction rate to include all the velocities.

References:

Freidberg, J. (2007). Plasma Physics and Fusion Energy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511755705

Krane, Kenneth S, and David Halliday. Introductory Nuclear Physics. New York: Wiley, 1988. Print.

Nuclear Fusion - Hyperphysics